Agriculture in Nigeria: 7 Interesting Facts & Statistics

July 24, 2024By Paul Akiwumi, Director for Africa and Least Developed Countries, UNCTAD

The high cost of nutritious food imposes a heavy burden on vulnerable households across the world, with African nations, especially the 33 least developed countries on the continent, hit the hardest.

The war in Ukraine is a key factor driving the recent skyrocketing of prices of staple foods like wheat, maize and barley. But food prices were already steadily increasing over the past 18 months due strong import demand and tightening export stocks, as a result of droughts in 2021.

Across Africa, the number of people experiencing food insecurity at a moderate or severe level increased from 512 million in 2014 to 794.7 million people in 2021 – nearly 60% of the continent’s population. Troublingly, at this pace, Africa is not on track to meet the food security and nutrition targets of Sustainable Development Goal 2.

Global challenges to moving affordable food, fertilizer and fuel are compounding with ongoing conflict in the region and drought. This puts pressure on already fragile livelihoods across the continent and raises the risk of additional population displacement due to lack of food.

Protectionism and trade disruption is hitting imports

For African countries, most of which are net food importers, food security is largely dependent on global markets. At least 82% of Africa’s basic food imports come from outside the continent. In Eastern Africa, 84% of wheat demand is met by imports.

Fertilizer prices have also more than tripled since January 2020, putting a strain on farmers across the continent. In Kenya, for example, rising fertilizer costs caused many farmers to abandon its use, until the government introduced a significant subsidy.

The closure of key trade routes, including the Black Sea, has dampened access to food staples and fertilizer. Furthermore, as global supplies become limited, traders are likely to favour larger markets, threatening access to smaller farms across the continent, which are nevertheless responsible for 70% of African food production.

Vulnerable populations, vulnerable land tenure

Despite the extremely challenging global context, homegrown challenges exacerbate Africa’s food security crisis. Africa is not realizing its own potential to feed itself.

In 2021, 52% of employed people in Sub-Saharan Africa were active in agriculture, and roughly 45% of the world’s area suitable for sustainable agriculture production expansion is located in Africa, but the lowest agriculture productivity per worker rates are found within the continent.

With production processes unchanged for many decades, most of African agriculture is still characterized by the farming of cash crops for export. For example, 14.8% of Côte d’Ivoire’s land is used for cocoa production.

While the world is reliant on Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa, which makes up 40% of global supply, the country reaps few benefits. The labour-intensive agriculture leads to minimal investment, and most of the 5 million people, approximately 20% of the population, who depend on cocoa farming for their livelihoods remain in chronic poverty. As Côte d’Ivoire dropped the farmgate price of cocoa by 17.5% last year, the disparity caused by rising food prices will intensify food insecurity across the nation.

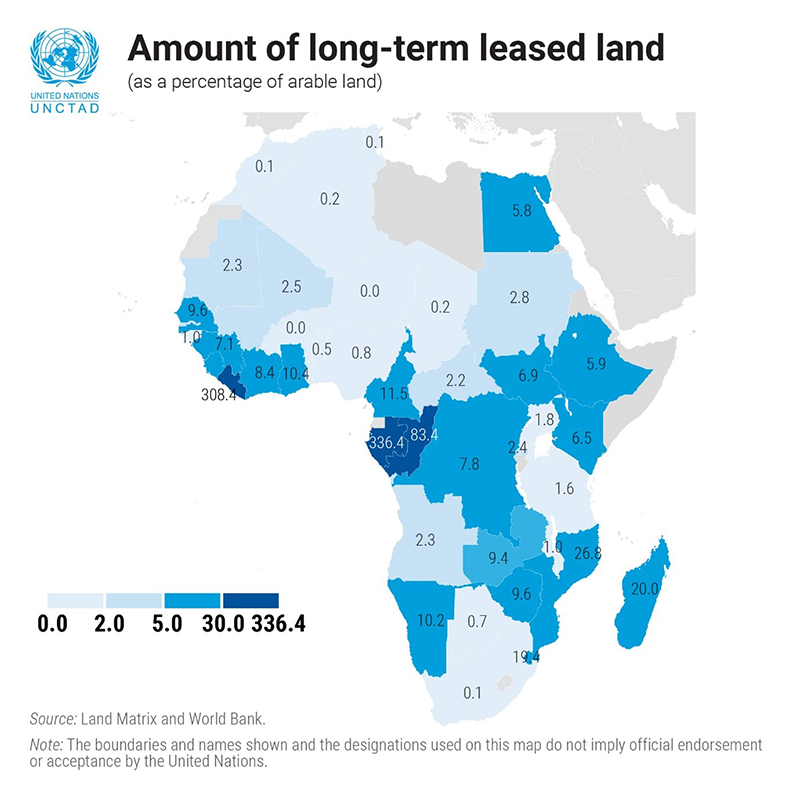

Another concern is that huge swathes of land are subject to long-term leases by foreign nations and private companies for the extraction of resources and the production of agricultural goods for export.

While the scale of these land deals is unknown and reports vary, there is evidence for alarm (see the figure below). Large-scale land deals in Africa totalled 22 million hectares from 2005 to 2017 and are likely rising.

Increased demand for agrofuels over the past two decades has added fuel to the fire. Despite arguments from foreign firms that long-term land leases can contribute to local development, case studies from Mozambique, Ghana and Madagascar have shown otherwise.

Agrofuel plantations displace communities, disrupt livelihoods, make minimal contributions to employment, exacerbate rural poverty and worsen environmental conditions through practices like deforestation.

These long-term land deals simultaneously take away the potential for local communities to use their land for productive purposes aligned with their own development visions.

In the absence of strong property rights and resource governance systems, commercial investments in agriculture can lead to displacement, loss of livelihoods and loss of access and tenure rights to land for the local population.

When land and other governance systems effectively protect these rights, the private sector, including smallholder farmers, can better allocate resources and make forward-looking investments in capital and other inputs, motivated by the promise of future returns.

Taking stock of efforts to transform Africa’s agricultural sector

The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) is Africa’s policy framework for agricultural transformation. Created in Maputo, Mozambique in 2003, commitments to prioritize food security and nutrition, economic growth and prosperity in Africa were further strengthened in the 2014 Malabo Declaration.

The commitments were reinforced through the development of Africa’s common position on food systems, to help deliver on targets of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals. Despite featuring across Africa’s development agenda, and the African Union dubbing 2022 as the “Year of Nutrition”, the continent’s performance remains subdued.

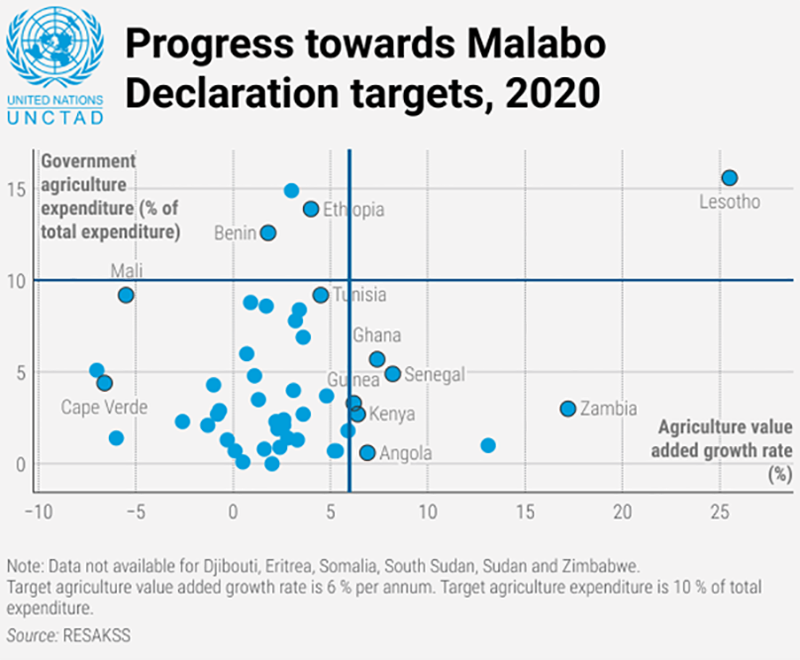

It was in Malabo that African countries adopted a resolution to commit at least 10% of their annual public budget to agriculture and rural development and to achieve agricultural value-added growth rates of at least 6% per annum.

A cornerstone of this ambition was the implementation of national agriculture investment plans (NAIPs) – country specific visions and strategies to put the CAADP agenda into practice. At the same time, AU heads of state and government committed to ending hunger by 2025 and resolved to halve the current levels of post-harvest losses by the same year.

In 2020, only four countries – Lesotho, Malawi, Ethiopia and Benin – had government expenditures in agriculture that met or exceeded the target of 10% of annual public expenditures.

Africa-wide, just 2.1% of public budget expenditures were dedicated to agricultural spending. Similarly in 2020, only eight countries met the 6% agricultural value-added growth rate target – Lesotho, Zambia, South Africa, Senegal, Ghana, Angola, Kenya and Guinea.

Africa-wide, the growth rate for agricultural value added was just 2.6% in 2020 (see the figure below). Overall, of the 51 member states that reported progress in implementing the Malabo Declaration during the 2021 biennial review cycle, only one country – Rwanda – is on track towards achieving the CAADP Malabo commitments by 2025.

Africa must act now

Increasing food insecurity across the continent comes with severe consequences for development, threatening the livelihoods of millions and making it extremely difficult to realize the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

It’s crucial for African governments and their development partners to seek solutions to weather the current crisis and address the deeper causes of food vulnerability across the continent.

This includes boosting efforts to meet the goals and targets of CAADP. Moreover, they need to shore up domestic production and regional trade, provide assistance and guidance on how to adapt to climate change, and ensure local resources serve local needs.

At the same time Africa’s trading partners should be aware of the crucial role they play in ensuring food security and avoid export bans.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) can help enhance agricultural trade and food security. The implementation of the AfCFTA, alongside targeted policies to boost industrialization and bolster the agro-industry in Africa, can spur the creation of much-needed jobs and entrepreneurship opportunities for local populations.

The private sector also has a compelling role to support agricultural trade, technology uptake and investment.

Also, there is a need to modernize countries’ agricultural strategies to generate new skills and technologies to enhance productivity and support agricultural workers. This includes supporting seed investments, opening new linkages with local producers and brokering collaboration between governments, international and domestic agriculture companies and smallholder farmers in Africa.

Modernization of Africa’s agricultural sector also requires concerted efforts to increase the value-added content of production. To achieve this, countries must prioritize the development of productive capacities.